An Interview with Adam Dant

An Interview with Adam Dant

Thursday 11th May 2023 | Joe

Metro Colour Printers kicked off a series of interviews for This is Shoreditch by featuring the talented local resident and visionary artist, Artista. Adam Dant, renowned for his intricate and captivating artwork, has left a lasting impression on viewers for over a decade. His unique style and meticulous attention to detail draw inspiration from a diverse range of sources, including history, mythology, and contemporary culture, resulting in pieces that weave complex narratives.

Dant's preferred medium, printmaking, allows him to delve into the technical aspects of planning, sketching, and executing his works with precision. Through his art, he fearlessly challenges societal norms and confronts uncomfortable truths, inviting viewers to explore alternative perspectives. Dant firmly believes in the transformative power of art, using it as a catalyst to provoke thought and ignite meaningful conversations, ultimately making a profound impact on society.

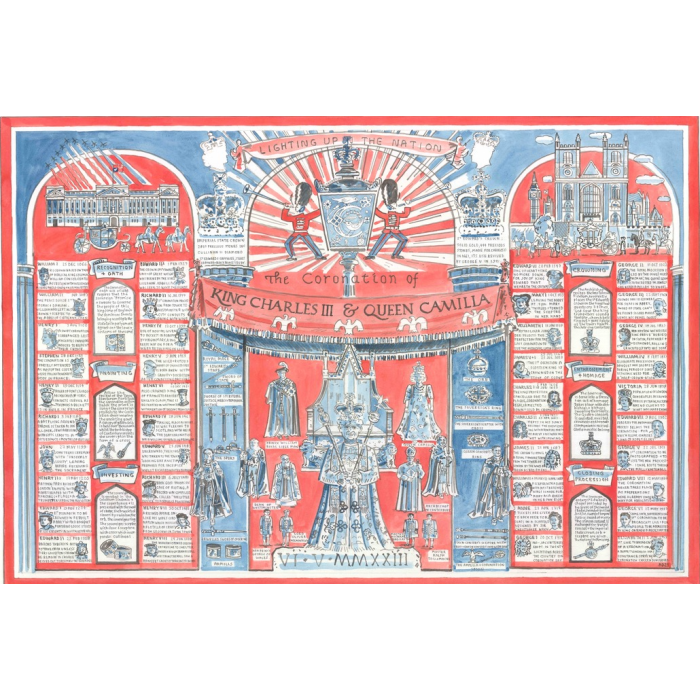

In addition to his exceptional body of work, Adam Dant has recently released a new print in anticipation of King Charles III's Coronation. This special piece pays homage to the historical and ceremonial significance of the event, drawing inspiration from the iconic architecture of Westminster Abbey, the traditional venue for British monarchs' coronations since 1066. The print skillfully captures the key individuals and rituals central to the coronation ceremony, embodying the continuity and profundity of this historic moment. It transcends partisan divides and offers a glimpse into the transformative nature of such an event.

With its rich detail and thoughtful composition, the print not only serves as a visually stunning work of art but also as a valuable historic artifact. It appeals to families, societies, and organizations seeking a meaningful memento that honors the enduring legacy of the British Crown. Adam Dant's ability to blend artistry, historical significance, and aesthetic pleasure is once again exemplified in this remarkable print, showcasing his position as an exceptional artist within the contemporary art scene.

Can you tell us about your background and how you became interested in art?

I was fortunate to be born in Cambridge which, for those who have not had the pleasure of visiting its dreamy spires and hallowed cloisters, is something of a fantasy realm, especially for a young child, whoever they are or whatever their background. I escaped 'normal life' by living in institutions such as The Fitzwilliam Museum, The Wren Library, Sedgwick Museum, etc., and later, in The Eagle Pub, Clare Cellars, or on a punt with a bottle of vin ordinaire, a harmonica, a girlfriend, and some pretentious reading material. When people asked me as a child what I was going to do with my life, I told them that the RAF wanted me and that I was going to fix Spitfires like my grandfather had done, but they wouldn't let me and told me I was an artist, and that was that.

Your artwork is known for its intricate detail and complexity. How do you approach creating such elaborate drawings?

When people around me realized that tying me to a chair was not going to stop me drawing, I was told that if that was what I was going to do, I'd have to learn to do it properly. I went to life drawing classes every night for years and years, studied perspective, technical drawing, graphic reproduction, etc., and took work providing very objective illustrations for Cambridge University Examination Board papers for what was then known as 'The Third World.' When I approach creating an elaborate drawing, all that stuff is there to start with now.

Could you walk us through your artistic process, from conception to completion?

Not without giving away all the trade secrets and the mystery. It's probably best for people who don't make art to stick to believing that it happens like it does in movies about artists, you know! Vincent Van Gogh is standing in a cornfield, flailing around and fighting crows then bang, suddenly it's all 'starry, starry night..

.

Your drawings often feature maps and historical references. How do you incorporate research into your artwork?

Some of my drawings require as much time to be spent in libraries and archives as in the studio. Often all this research and reading ends up as a long list. When everything on the list is ticked off, then the drawing is finished.

You've lived in Shoreditch for many years. How has the neighborhood changed since you first moved there?

I moved to Shoreditch, specifically Redchurch Street because I was working with various print processes, and that's where all the printers were. Lithographers, Foil Blockers, bookbinders, letterpress printers, and even a guillotine blade sharpener were all on the same street busy doing all manner of things mainly for City of London firms. I'd come along and ask them to do odd stuff, mess about with their usual processes, like printing my banknotes, or printing with no ink. Everyone used to stop for lunch at Ron's cafe or next door in The Owl and The Pussycat pub. I no doubt first met Danny from Metro Imaging in the greasy spoon caff. Metro imaging seems to have survived in the neighbourhood while every single one of the other printers has vanished and been replaced by beard moisturizing operations or yet another bloody coffee machine. A supposed ancestor of mine was a printer round here called Danter who had his presses confiscated for printing pirate copies of Shakespeare plays. A bit like the man with a camcorder in the Rio cinema would pop up on Brick Lane with copies of the latest Tom Cruise movie the following Sunday. Printing might well be in the blood of the neighbourhood, I’d like to think so, William Hogarth trained as an engraver in Spitalfields and Gilbert and George have just opened their museum in Brick Lane. We mustn’t forget that this is still the Shoreditch where Shakespeare created his great works, and who's going to last longer, Shakespeare or Foxtons ?

What draws you to Shoreditch as an artist?

Everyone who lived here in the late 1980s and early 90s assumed the neighbourhood would eventually be swallowed up by The City of London. Shoreditch, as a hub of light industry and the centre of the cabinet-making trade, started dwindling after all the chaps were killed in the First World War. By the time the recession arrived in the 1990s, it was pretty much deserted. An estate agent called James Goff managed to persuade young artists to move into the area. Everything was in a terrible state, and there was only one pub to go to on a Saturday night. Anyway, Redchurch St is in Bethnal Green, in the parish of St. Matthew's, so not really Shoreditch.

Your artwork often comments on social and political issues. How do you use your art to address these topics?

Living in this neighbourhood often feels like being at the epicentre of the events of the day because of its proximity to the City of London and its attraction for all sorts of reasons to all sorts of people. I quite often draw in the street when I'm out and about and look for how the issues of general 'politics', 'social change,' and 'social control' become visible as part of the everyday. When you pair the observable with the way the media report on various topics, the apparent 'disconnect' prompts further investigation. I was making drawings in Canary Wharf during the 1998 financial crisis. Reading the newspapers, one would have imagined that the place resembled the gates of hell, while in reality, it was just a bunch of sad-faced men and women wandering around carrying boxes full of novelty mugs, pairs of trainers, and photos of the dog.

Can you speak to the relationship between art and gentrification, particularly in Shoreditch?

I have no idea with the current status of art in the gentrified now. I don't think I'm really in that bit of the 'art world'.'

Your work often incorporates humor and satire. How do you use these elements to convey your message?

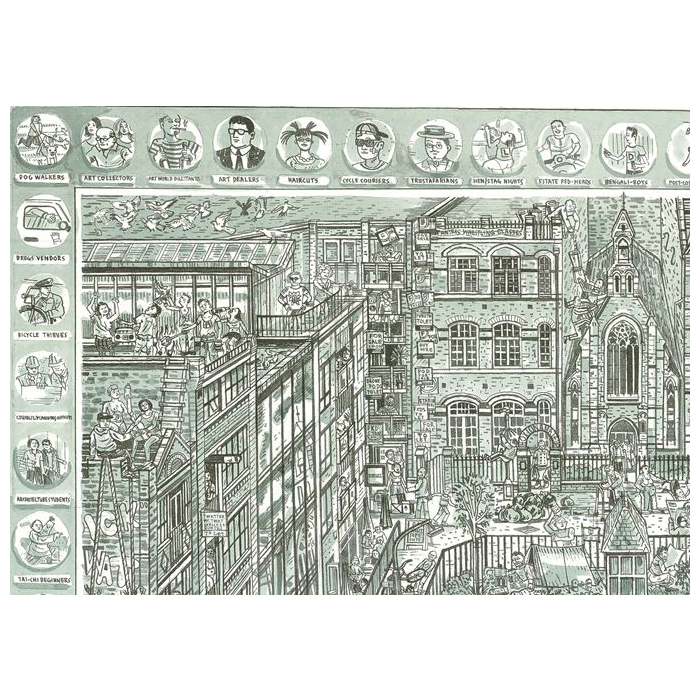

I used to make a lot of large drawings, that were full of 'gags', with the intention of making people laugh. The scenarios I depicted were ridiculous, but all came from real life. Images of accidents waiting to happen, set-ups like early cinema, or literalist depictions of figures of speech in the manner of Bruegel, Van Der Borcht, Teniers, et al. In the National Gallery, I looked at how little time the visitors spent in front of paintings and wondered how I could sustain their attention for as long as it took to watch the latest Hollywood blockbuster but, solely with the use of a bottle of Indian ink and a number three brush. The drawings became an exercise in problem-solving through densely wrought visual narrative.

Can you tell us about your experiences exhibiting your artwork in different settings, such as galleries and public spaces?

Before I worked with galleries, I used to produce a newspaper as a work of art and hand it to passers-by in the street. It was called Donald Parsnips Daily Journal, it was an A6 8-page stapled pamphlet in the style of an early 'chap book,' and I made 100 copies of it every morning at Frank's 2p copy shop from 1995 till the millennium. I worked in an Old Master Picture gallery on Old Bond Street at the time and would distribute this newspaper/work of art during my walk from Bethnal Green to Mayfair. The Arts Council, national collections, and arts organizations were banging on about 'seeking arts new publics'; they probably still are. I thought it was simpler to just go into the street and 'Look! there they are.'

The newspaper bore the motto "Take it of Leave", it was all a bit stupid and annoying, but was sometimes extremely funny. An American collector commissioned 13 archival boxes of facsimile copies to be produced. These are now in The Tate, MOMA, The British Museum etc, so the whole performance ended up being detained in a cultural institution, in the end.

Your artwork includes both fictional and real elements. How do you balance these two aspects in your work?

If you go far enough back in history, you must decide how much belief you want to ascribe to what most would consider tall tales and bizarre myths. I've just finished a rather fancy painted interior for a Medieval Manor House in Monmouthshire. The images are based on Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain, which tells the story of how Brutus of Troy founded Troia Nova, which became London, and how the British Monarchy is descended from the goddess Aphrodite and, essentially, from the God Mars. I'm happy to go along with that, although Iman Jacob Wilkins' theory in his work "Where Troy Once Stood," that the ancient city was located just on the outskirts of Cambridge, is pushing it.

How do you approach creating a sense of place in your drawings?

I made a drawing of Sloane Square as it is now, with all the various types of people and activities that one would find there. Fortunately, Cafe Colbert has a very nice terrace from which to observe all the goings-on. They serve a very good breakfast of Boudin Noir and a fried egg, and in the summer, they make their own raspberry sorbet.

Your drawings often feature crowds of people. Can you speak to the significance of this motif in your work?

I've always beeen interested in observing colonies of ants, and when I lived in Rome, I'd spend days on end, at the zoo, looking at the goings-on in the monkey pit. I don't think of human existence as being like, that of either ants or primates at all. So, in my drawings, I'm trying to depict the unique character of our species, not according to the imperatives of eating, crapping, scrapping, and fucking, but as imbued with the more subtle contingencies of agency, empathy, love, and progress

.

How do you see your artwork evolving in the future?

I'm being told to paint more. I've completed quite a few decorative schemes for very old houses, and quite enjoy the perceived permanence of this kind of art. Having spent time in Italy where they didn't let a bunch of crazed wackadoodle, fanatics smash the crap out of everything they didn't like quite as often, as has happened over here, I'm attempting to provide redress with a contemporary reinvention of the tradition of the country house painter, basing designs on the fragments that are left over.

How do you approach each commission you receive, particularly ones like the Barts Hospital project?

Many of the drawings and other works of art I make are researched and constructed in collaboration with specific groups of people, as well as with the public in general. I've just unveiled a huge drawing that commemorates and celebrates the 900th anniversary of St Bartholomew's Hospital in Smithfield. This involved collecting and illuminating 900 stories. So, in addition to my own research, I worked with the Barts archive, the heritage 900 team, the hospital community of surgeons, nurses, volunteers, former patients, and we put out a call through the media for personal stories about the place. All the members of one big Irish family called the Murphys from Islington had visited the hospital at one point or another, from the youngest who'd collided with some railings after trying to run home as fast as he could with his eyes closed, his brother who'd been "bitten on the eye" by a dog, and his sister who'd managed to get her door key stuck in her ear.

Can you walk us through the creative process of creating a dwarfing artwork, from conception to completion?

It's too stressful to even think about it.

What advice would you give to aspiring artists, particularly those interested in pursuing a career in drawing?

Never take a job where there's any possibility of getting promoted.

You can find more of Adams Work at Tag Fine Arts - https://www.tagfinearts.com/artists/adam-dant/

Metro Colour Printers Shoreditch- www.metrocolourprinters.co.uk