Could You Live A Year Without Your Things? - 'My Stuff' Documentary Review

Could You Live A Year Without Your Things? - 'My Stuff' Documentary Review

Other | Friday 5th December 2014 | Ben

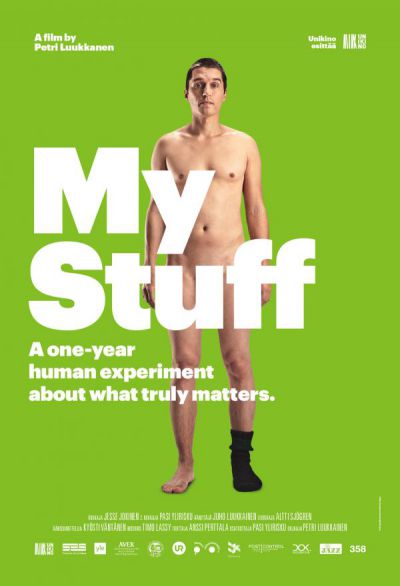

On Thursday, Guestlist went to see My Stuff (Tavarataivas in Finnish), a documentary about a man's exploration of his relationship with his belongings and how they affect his relationship with people. Put on as part of an exciting program by the brilliant Nordic Film Festival, the film was shown in the wonderful ArtHouse Crouch End cinema.

Guestlist went into the screening with a sense of anticipatory catharsis. We all have those moments of caprice when we imagine a life not weighed down by our earthly possessions. No television, no closet full of different coloured denim jackets and even no bed, very alluring. However, as we begin to convince ourselves that we could live like Tom Hanks in Cast Away, our ringing mobiles remind us that we actually lack the courage to make that leap. However, Petri Luukkainen made that leap. His idea was simple: lock all his belongings in storage and not spend any money for a year. He allowed himself to take out one item a day, but that’s it.

There were no half-measures (at the start anyway), so the film opened in comedic fashion with a stark-naked Luukkainen running down flights of stairs and through snowy streets to retrieve his first possession. Guestlist lazily assumed Luukkainen would grab a pair of underpants. It became apparent that Guestlist knows nothing about foresight when Luukkainen chose a large winter coat instead; underpants would not keep you warm on the cold hard floor during a Finnish winter. This led to one of the funniest moments of the film when a cold and uncomfortable Luukkainen realised that he would be much warmer during sleep if he put his legs through the sleeves of the coat.

The first 20 minutes of the film involve Luukkainen making a lot of tough choices: trousers or duvet? His friends, bemused by his experiment, suggest the versatility and merits of different possessions, a duvet by night, curtain by day? By this stage he has already begun using his window-ledge as a fridge. The absence of such luxuries made him more appreciative of everything we take for granted – rarely has a man been so moved by the sight of a mattress.

Therefore, it is unfortunate that the film doesn’t dedicate more time to the early days of the experiment. Luukkainen flits over the difficulties of maintaining social contact without technology and the effects of the experiment on his work-life. Furthermore, one of the film’s most defining features, the retrieving of an item a day, turns out to be its biggest flaw. As the days rack up, Luukkainen retrieves more and more items to the point where the dilemma of choosing possessions quickly dissipates, and the experiment ossifies. What we are left with is a man whose experiment no longer has any serious impact on his way of life; he is now simply living a mildly inconvenient lifestyle. That is surprising considering the weight given to the conversations he has with his grandmother about what possessions are important. Her remarks "stuff doesn't make you happy" and other sentiments that can be neatly labelled under the adage 'money doesn't buy you happiness' are undermined with each newly retrieved item. Several times Luukkainen notes that weeks pass by between his storage visits. Evidently he has reached a stage where he worked out what he needs, so all the items remaining in storage are not essentials but luxuries that can be abstained from. This begs the question: if 'stuff' doesn't make you happy and you don't actually need anything else, why keep going back to get more? The film doesn't present a satisfying answer to that question.

However, where the film does succeed is in the more subtle plot of monetary abnegation. It can be argued that that is a much more important lesson than the limiting of belongings. By abstaining from spending money Luukkainen stumbles upon a refreshing independence. When his dishwasher breaks down he fixes it himself. When a bike lock needs to be opened he spends five hours hacking and sawing it open. Five hours, but he did it all by himself. It’s a quietly powerful example of how easy it is to break away from being reliant upon others. He only worries about breaking his rule in one instance. His girlfriend’s fridge breaks beyond repair and Luukkainen was faced with difficult choice, the first for a long time.

Luukkainen’s exploration of the effects of avarice and consumerism is not a novel idea by any means. Morgan Spurlock dived into it stomach-first and YBA Michael Landy systematically destroyed all 7,227 of his possessions in 2001. However, there is something charming and appealing about Luukkainen’s contribution to the discussion. Perhaps it’s the fact that it is a much more feasible idea for a viewer to pursue. Eating fast food for breakfast lunch and dinner is very taxing on the body. Destroying all your possessions is too extreme and absolute, but locking up your posessions temporarily may appear to be quite doable. Or maybe it’s the romance leitmotif that simmers throughout the film. It’s probably that. We’re all suckers for love.

7/10

Have a look the trailer:

By @benjyrabs